“From a flat bar of soft iron, hand forged into a gun barrel; laboriously bored and rifled with crude tools; fitted with a stock hewn from a maple tree in the neighboring forest; and supplied with a lock hammered to shape on the anvil; an unknown smith, in a shop long since silent, fashioned a rifle which changed the whole course of world history; made possible the settlement of a continent; and ultimately Freed our country of foreign domination.

Light in weight; graceful in line; economical in consumption of powder and lead; fatally precise; distinctly American; it sprang into immediate popularity; and for a hundred years was a model often slightly varied but never radically changed.

Legend regarding this rifle which have never been confirmed have drifted out of the dusty past; inaccuracies have passed for facts. Few writers have given more than a passing word to a weapon which deserves a lasting place in history, and it is a pleasure to present herewith the data collected during the past ten years and to dedicate this work to the KENTUCKY RIFLE.”

—- Capt. John G. Dillon, 1924, From his book The Kentucky Rifle

It is hard to beat John Dillon’s description of an Kentucky Rifle, the popular name for the American longrifle. This hints at the fact that there are a lot of names for basically the same thing. There is even some disagreement as to whether you spell it longrifle or long rifle. Generically, we refer to the American longrifle which includes all longrifles made in what would become the United States of America. We refer to longrifles made in specific States or regions by adding the State or region names such as in Pennsylvania longrifles or Southern longrifles; or even Kentucky longrifles, not to be confused with Kentucky Rifles. Remember that Kentucky Rifles is the popular name for all longrifles and is equivalent in use to American longrifles.

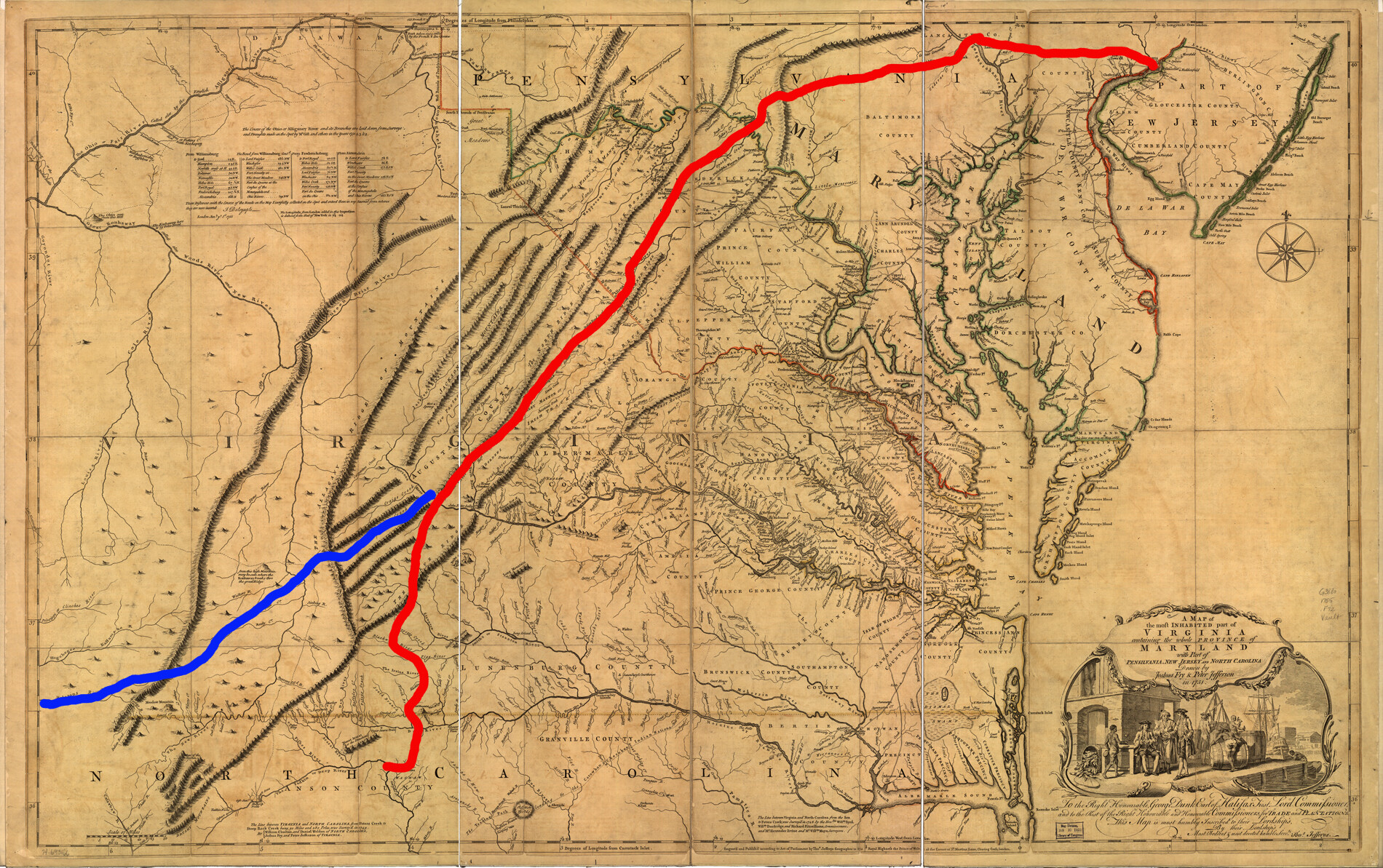

The American longrifle originated in and about Lancaster, Pennsylvania in the second quarter of the 18th century and was made well into the second quarter of the 19th century. Martin Mylin, a German Swiss gunsmith, established a shop outside Lancaster in 1719, and is credited with making the first American longrifle about 1740. Eventually, the American longrifle gave way to more sophisticated, mass produced firearms starting with the Industrial Revolution in America around 1840. However, production of the American longrifle never completely ceased. Gunsmiths were making similar guns throughout the 19th century. Mostly, these were high end target rifles, but there were back country gunsmiths making longrifles for subsistence hunting in the Appalachians well into the 20th century. With the renewed interest in all things early American in the 1920’s and 30’s (the Colonial Revival period) as a result of the American sesquicentennial, there was a renewed interest in the Kentucky rifle. It was during this period that John Dillon wrote his book heralding an ever increasing interest in collecting, and recreating these uniquely American firearms.

But I still haven’t really told you what makes a gun an American longrifle. Well, they are long (usually five feet or more), graceful, slender, exceedingly accurate (by the standards of the day), muzzleloading (gunpowder and a round lead ball covered by a cloth patch were loaded from the muzzle(front) of the barrel), rifled (spiral grooves (furrows) were cut into the bore of the barrel to impart a stabilizing spin on the bullet thereby dramatically increasing accuracy), of relatively small caliber (average was around 50 caliber, decreasing into the 19th century), with either flintlock or percussion sidelock ignition systems, a full length wood stock, and usually a patchbox or grease hole on the lock side of the butt stock. The barrels were almost always octagon (“squared” in 18th century terminology) and tapered toward the muzzle and flared back out starting a few inches from the muzzle. This taper and flare (swamp) was generally very subtle giving way to straight tapered and then straight barrels in the mid 19th century. These guns were primarily mounted with brass fixtures (butt piece, toe plate, guard, side plate, thimbles and nose piece); but some, most notably in the South, had iron mounts; and, very rarely, there was a silver mounted gun. Many of these guns were decorated with baroque and rococo carving and engraving as well as inlays of silver and brass wire and sheet. Some of these rifles were extremely ornate and were one of the first truly American art forms. They are now recognized as a significant form of American decorative art and people collect them as such. This is what has driven the price of the best original flintlock American longrifles well into six figures.

The roots of the American longrifle are in the German rifles, or Jaegers, that were brought to this country by early German settlers and gunsmiths. Among other stylistic changes, the barrels of the Jaegers were lengthened, and the caliber reduced to produce the uniquely American longrifle which made more efficient use of powder and was very accurate at long range. The American longrifle developed to serve the needs of commercial hunters traveling to the frontier and beyond to harvest deer skins for export. These commercial hunters or “longhunters” have long been portrayed as pioneers and explorers of European origin such as Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett. However, there is good reason to believe that as many as half of the early longrifles went to native American hunters who had been using European arms to harvest skins for export to Europe since the first contact with European traders in the 16th century.

There is lots more that I could write about the American longrifle, but the best way to learn about them is to look at them and handle them. On this site you will find photos of some of the better ones that I have made in my Portfolio as well as photos of original longrifles that I and others have owned in the Antique Longrifles Gallery. Look them over good, get some good books on the subject, and seek out original longrifles for study at museums, gun shows, and private owners.

Bibliography

- The Kentucky Rifle by Capt. John Dillon

- The Kentucky Rifle in its Golden Age by Joe Kindig Jr.

- Rifles of Colonial America, Volume 1 & Volume 2by George Shumway

- Recreating the American Longrifle by William Buchele, George Shumway, and Peter Alexander

- The Gunsmith of Grenville County, Building the American Longrifle by Peter Alexander

- The American Rifle: At the Battle at Kings Mountain by C.P. Russell, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Washington, D.C., 1941

- Rifle Making in the Great Smoky Mountains by Arthur I. Kendall, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Washington, D.C., 1941

Comments are closed.